Creating Space for and with Animals

In Life and on the Page

My Dear Literary Animals,

I have been thinking about the ways we create and share space with our fellow animals in life and on the page.

Earlier this year, I had the pleasure of attending the Animal and Vegan Advocacy Conference, in Alexandria Virginia. I was on a panel moderated by Martin Rowe, Executive Director of the Culture and Animals Foundation (CAF) with fellow CAF grantees, Kittie Mae Morris and Allison Argo.

Kittie Mae is a brilliant dancer whose piece “Blue” was inspired by Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ Undrowned. (How cool is that?) Allison Argo has built an extraordinary career making films about animals including chimpanzees, elephants and farm animals. Her current film: Forever Home, documents Piedmont Farm Animal Refuge in North Carolina, which not only creates space for rescued farm animals, but asks and answers the question: What does animal-centered design look like?

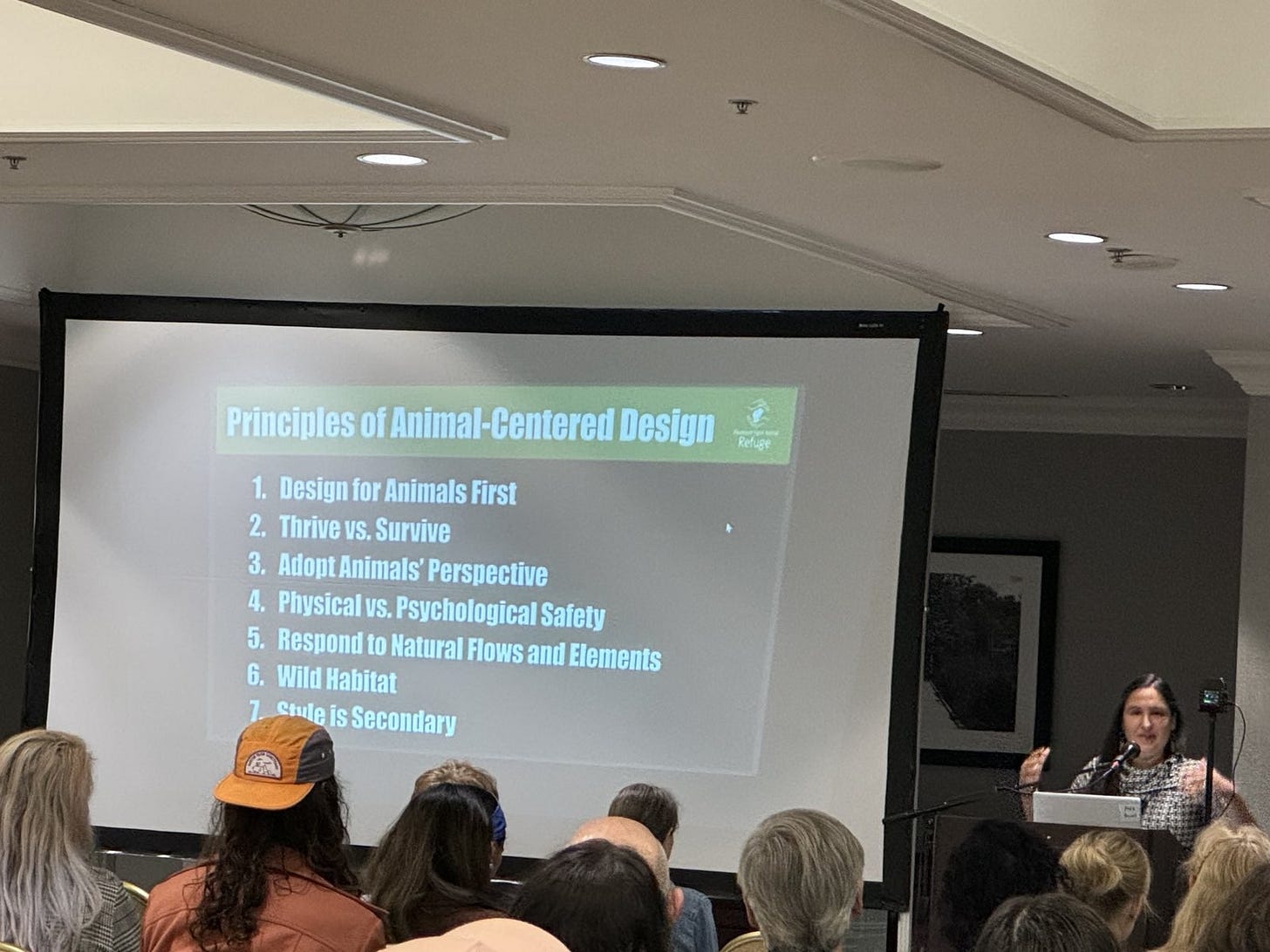

The next day, Lenore Braford, from Piedmont Farm Animal Refuge was on another panel, spoke more about animal-centered design.

Unlike factory farms which are designed around industry profit, this farm refuge looks to incorporate what makes animals thrive, so they can not only be safe but feel safe.

I returned from the conference to my work in bringing nature-based solutions to urban stormwater planning. How our practices here, incorporate plantings to support wildlife habitat, how our designs can include features like turtle basking stations and perches for Osprey, and how our restored waterways allow the return of so many species.

How can we think about these principles of animal-centered design in art?

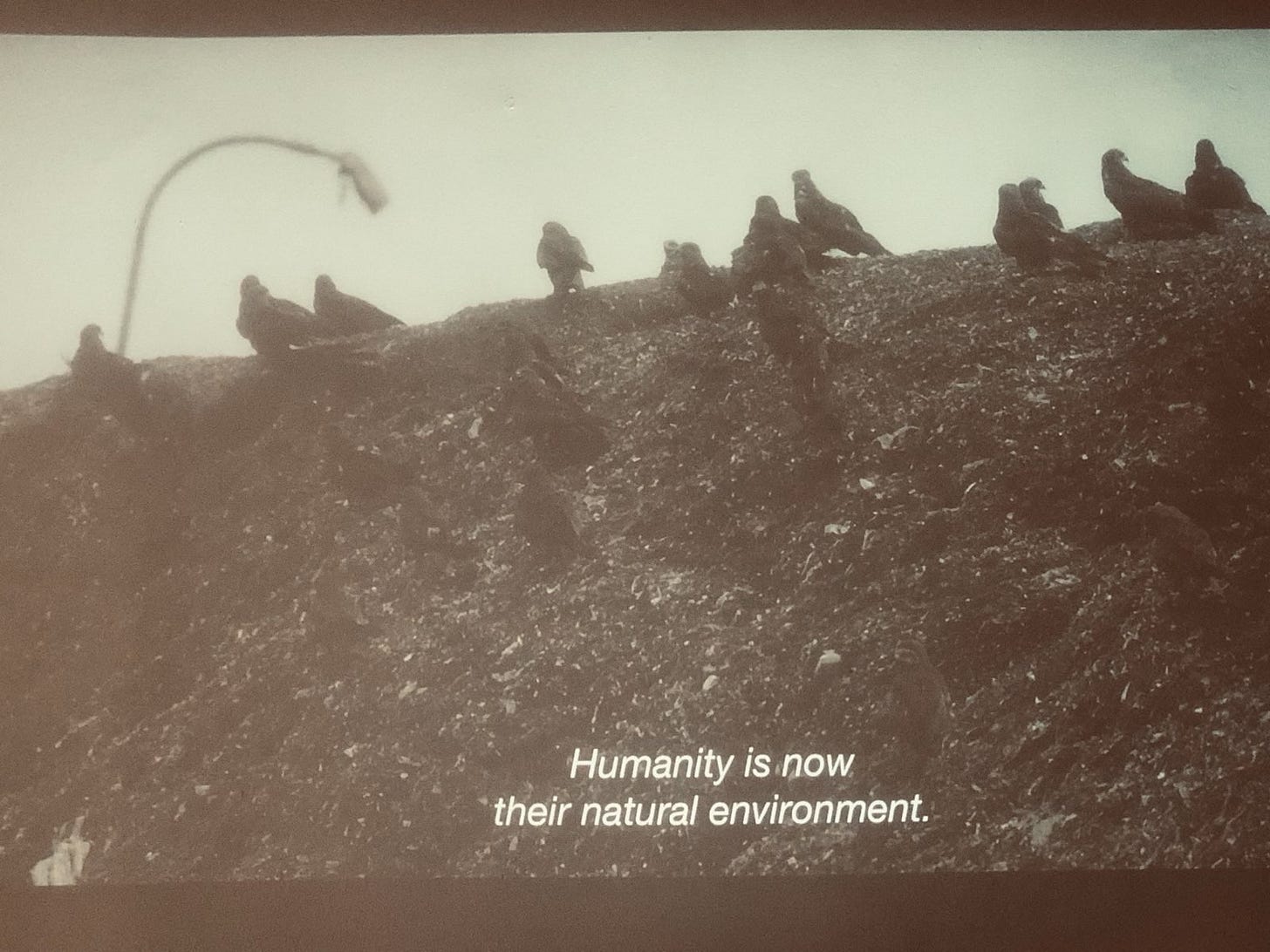

I return to Shaunak Sen’s brilliant and poetic film, All That Breathes, which follows two brothers, Mohammad Saud and Nadeem Shehzad, who live in Delhi and tend to injured kites, who fall from the sky every day due to heat and pollution. The film opens capturing the voices of the city’s animals— insects crawling, dogs barking, rats squealing, mosquitoes buzzing, pigeons cooing, goats bleating, chickens clucking— alongside the rumbling engines and car horns. “Humanity is now their natural environment, ” one of the brother’s reflects. “Song birds sing at a higher pitch to communicate over traffic noise,” he says. “Every life form adjusts to the city now.”

It was their mother who instilled in them “One shouldn’t differentiate between all that breathes.” Shanauk Sen described these brothers as “Philosophers of the Urban,” and the film is filled with their attuned insights:

“You don’t care for things because they share the same country, religion or politics. Life itself is kinship. We’re all a community of air.”

A Community of Air

I’ve been thinking about both this community of air and animal-centered design, while reading the opening chapter of Kyoko Mori’s Cat and Bird, a “memoir in animals.”

Mori lives in Washington D.C, where migratory swifts pass through. She notes one major threat is “the difficulty of finding a place to sleep during their fall migration.” She explains:

“ The old trees in whose hollows they once rested as they traveled south in enormous flocks are long gone. The first houses with chimneys that replaced the forests have been torn down as well. New houses built in their place have chimneys with ceramic interiors too slippery for the birds feet, which leaves old buildings, like my brownstone in the nation's capital, as their only roosting sites.”

But many buildings cover their chimneys to keep birds out or turn on their heat too early in the fall, which will roast these birds. Kyoko Mori finds a way to allow her building to become a safe resting spot for the swifts:

“The easiest way for me to ensure that our chimney stayed open and the boiler got turned on only after the birds were gone (and turned off before they came back-though in smaller numbers-in late April or early May) was to be in charge of making and carrying our the building's heating policy, so I volunteered to be on our co-op's board of directors and stayed on as president to protect the swifts..”

As she notes in her prologue: “I have to believe that from our shelter on the ground, I can help keep their wings beating.”

Other Literary Animal News

An abridged version of my conversation with Parul Kapur on her novel Inside The Mirror (which was just long-listed for both the Center for Fiction 2024 First Novel Prize AND the New American Voices Prize!!) was published in World Literature Today: “All Art Is History”: A Conversation with Parul Kapur”

Parul and I spoke at Yu and Me Books and enjoyed an amazing meal at Bodhi Vegan afterwards. I want to share with you a literary animal question I asked her that night:

SI: I'm interested in how animals are portrayed on the page. I’m always reading through that lens and paying attention to animal details. Though not the focus of this book, you do pay attention to the lives of animals. I am curious how you were thinking about bringing animals into this story.

PK: What really strikes me and breaks my heart in India is the stray dogs. You can't help but see them wherever you go. They're very sweet, very gentle. And there's one I describe in the book that is in an awful condition— he's suffering but not dead—with mange and other things. That was a dog I had seen on the street. My parents had a house in India they would sometimes go to and I saw that dog around there. He made such an impression on me. The suffering of those poor innocent animals—they're very vulnerable—was a metaphor for the larger suffering in the society… The society had been impoverished by British rule, then there had been the cataclysm of Partition. So many millions of people left homeless. There was an incredible amount of suffering.

What I’ve been reading:

My dear readers, I am working on more literary animal programming about the ways we create and make space for animals especially in the urban context and with a changing climate. Stay tuned. I’d also love to hear from you and how you are thinking about these things in life and on the page.

Yours for the Animals,

Sangamithra